“I always felt pressure before a big fight, because what was happening was real” - Muhammad Ali

Sport is a fascinating and ideal environment in which to study stress. The role that stress and emotions play in sport is often illustrated by the archetypal image of an athlete choking; snatching defeat from the jaws of victory. But stress and emotions can also help athletes perform well. For psychologists interested in helping athletes deal with the challenge of competitive sport and maximize potential an understanding of stress and emotion is clearly advantageous. While helping athletes achieve their potential is a worthy endeavour in its own right, the study of emotion in sport is also important because it can provide lessons that are applicable to other performance settings where tasks are also difficult and achievement is important to the individual, such as education, the performing arts and business.

In sport stress and emotion are not just abstract theoretical concepts removed from the real world but reflect the actual thoughts, feelings and experiences of athletes as the following quotes attest.

“In snooker the conditions are always perfect. All we have to do is knock a ball into a pocket, something we practise over and over again. But snooker can still cut a professional to bits. He’ll be standing over a table, and he’ll suddenly notice. His hands are shaking. Yeah, he’s shaking like a ... leaf.” - Six-time world snooker Champion Steve Davis

“It was an important moment for me, the nation and the team ... but I’ve never felt pressure like that in a game before. I just couldn’t breathe.” David Beckham talking about taking the penalty against Argentina in the 2002 World Cup.

“I truly don’t know how I made the final putt, I was definitely shaking” - Ernie Els describing his feelings as he holed a 3 foot putt to win the 2002 British Open

“I watched a bit of CSI Miami in the Olympic village to try to take my mind off the race ... My nerves were really bad when I got to the pool. I had to keep lying down because I thought I was going to be sick ... but as soon as you dive in, the only thing you think about is the strokes, consistency and telling yourself, ‘Don’t mess this up’.” - Gold medal winner Becky Adlington talking about how she felt before 800 metre freestyle in the 2008 Beijing Olympics.

Sport is an ideal environment within which to study stress and emotion for three reasons. First, the sporting environment is stressful and creates intense emotions that may otherwise be difficult to manufacture. Athletes are typically highly motivated to succeed, whether engaging for fun, pleasure or performance. However, success is not guaranteed and the emotions experienced cover a spectrum from the joy of victory to the dejection of defeat. Certainly it is difficult to replicate the intensity of a meaningful competitive event in a laboratory environment. Second, the ability to cope with stress and regulate emotions is seen to be central to success (Patmore, 1986). So sport provides an opportunity to explore how stress and emotions influence performance. At the highest level it is proposed that psychological factors, chief among them an ability to cope with stress that is the defining predictor of success (Orlick & Partington 1988). Third, sport has a wide range of performance environments that test abilities as diverse as physical prowess, effort, courage, technique, reaction time and complex decision-making and is an excellent context within which to explore how emotions influence a range of performance aspects. Even minor fluctuations in each aspect may result in substantial changes in performance and outcome. For example, a slight alteration in a golfer’s putting stroke from an increase in anxiety-induced muscular tension may be the difference between a successful or unsuccessful putt.

Because of this while the favourite often wins, sport can also be gloriously unpredictable. It is this uncertainty that makes sport such an interesting spectacle for spectators and also so stressful for athletes, as the following quote from Muhammad Ali attests:

“Boxing isn’t like a movie where you know how things will turn out in advance. You can get cut; you can get knocked out; anything can go wrong.”

The Stress Process

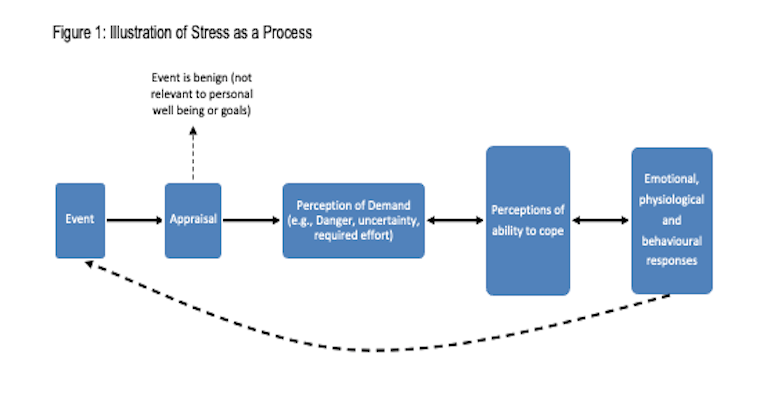

An understanding of stress helps to shed light on athletes’ responses to competition. Stress is best conceptualized as a process (cf. McGrath, 1970) and not an outcome nor an event. There are many process views of stress but broadly stress describes an individual’s appraisal of an environmental event as demanding and their ability to cope with the demanding event. A pictorial representation of the stress process is shown in image with this blog.

Stress need not necessarily be a negative experience. For example, Selye (1974) distinguished between eustress (good stress) and distress (bad stress). Further, Lazarus (1966) proposed three types of stress (two negative and one positive) depending on the appraisals made; Harm/Loss, Threat and Challenge. The stress process is dependent on there being an event to be appraised as demanding (see Task 2). Literature on understanding sources of stress (stressors) has typically used a qualitative approach to gather data from athletes. Using a qualitative approach helps to gather rich data about athletes’ experiences. A sample of the published literature on athletes’ sources of stress is included in Table 1 overleaf:

Authors | Sample | Sources of Stress |

Scanlan, Stein and Ravizza (1991) | 26 former ice skaters, comprising 4 novice, 6 junior and 16 senior athletes. |

Negative aspects of competition (81%). Negative significant-other relationships (77%). Demands or costs of skating (69%). Personal struggles 65%). Traumatic experience (19%).

|

Gould, Jackson and Finch (1993)

| Experiences of 17 National U.S figure skating champions (1985 – 1990) after becoming national champions. |

Relationship issues (82%). Expectations and pressures to perform (88%). Psychological demands of skater resources (53%). Physical demands on skater resources (47%). Environmental demands on skater resources at elite level (65%). Life direction concerns (35%). Miscellaneous sources of stress . |

Noblet and Gifford (2002) | Data from 32 Australian Rules Footballers (8 interviews, 4 focus groups). |

Negative aspects of organizational systems and culture Worries about performance expectations and standards Career development concerns Negative aspects of interpersonal relationships Demanding nature of the work itself Problems associated with work/non-work interface.

|

Campbell and Jones (2002)

| Data from 10 elite male wheelchair basketball players identified 10 general dimensions

|

Pre-event concerns Negative Match preparations On-court concerns Post-match performance concerns Negative aspects of major event Poor group interaction and communication Negative coaching/style behaviour Relationship issues Demands or costs of wheelchair basketball Lack of disability Awareness

|

Rainey and Hardy (1999) | Survey Data from 682 Rugby Union Referees. |

Performance concerns, Time pressure, interpersonal conflict.

|

What stands out from this research are the range of stressors. Not only are the ‘traditional’ stressors of performance expectations there, but so are others that are more distantly related to actual performance. These include personal relationships, group interaction and organisational stressors. These illustrate why sport is stressful and why the ability to cope with the sources of stress in a positive manner is so crucial to success.

Understanding the stress process is important because of the emotions that result which in turn influence our social interaction, behaviour and ultimately performance. Stress and emotion are inextricably linked and where there is stress there is emotion (Lazarus, 1999). Although it is probably worth pointing out that this is not always the case in reverse as sometimes positive emotions can occur in the absence of stress (Lazarus, 1999). One emotion of particular interest in sport settings is anxiety and this is hardly surprising give the importance that many athletes attach to performing well.

Exploring the Anxiety-Performance Relationship.

Before considering how anxiety occurs and relates to performance we should consider the physiological responses that can occur in sport settings. There is a history of research outlining that physiological changes may be unique to specific emotions (e.g., Ax, 1953) and that activation of the sympathetic arm of the autonomic nervous system may be associated with intensity of feeling (Hohmann, 1966). In short, feedback from the autonomic nervous system is central to emotion (cf. Damasio, 1995) and this section we first describe the nature of these changes and then consider how it may influence performance.

The Autonomic Nervous System

Key elements of an individual’s response to stress are changes in the Autonomic Nervous System. The Autonomic Nervous System controls functions of the body that are geared to survival and connect with the involuntary muscles such as, lungs stomach and kidneys (Gatchel, Baum & Krantz, 1989). The ANS is part of the peripheral nervous system which refers to all the nerves outside of the Central nervous system (Brain and Spinal cord). The Peripheral nervous system comprises the somatic system (connection with the voluntary muscles) and the Autonomic Nervous System. Both the Autonomic Nervous System and the somatic system are influenced by the central nervous system.

The ANS can further be subdivided into the sympathetic and parasympathetic branches. The sympathetic branch is responsible for mobilizing the body ready for action. The classic flight or fight response which is associated with the emotions of anger and fear (Canon, 1931). Because this response is geared towards sustaining an attack or fleeing it is a short-term response and places a strain on the body, which is why prolonged anger and fear carry the potential for harm (Lazarus, 1999). The parasympathetic nervous system is concerned with calming, or reducing the arousal. The activity of the sympathetic nervous system is generally all or nothing, that is the entire body is affected, and is long lasting, while the parasympathetic activity is short-lived and can affect individual organs in a more or less isolated manner (Gatchel et al., 1989).

The sympathetic nervous system exerts its influence through hormonal activity. Stimulation of the adrenal medulla (centre of the adrenal gland) results in secretion of adrenaline and noradrenaline (epinephrine and norepinephrine). The Pituitary Gland also releases adrenocorticotrophic hormone (ACTH) that stimulates the adrenal cortex (outer part of the adrenal gland) to release corticosteroids, and the one most often considered in response to stress is cortisol.

This overview outlines the basics of the stress process in sport. We hope you find it useful. Related to stress is anxiety and arousal and in other blogs we explore the link between arousal and sport performance with a focus on Drive Theory, the Inverted U Hypothesis, and also more complex models of anxiety-performance relationship, including the Individualised Zones of Optimal Functioning, Catastrophe Theory, Reversal Theory, and the Multidimensional Anxiety Theory.

Selected References

Ax, A. F. (1953). The physiological differentiation between fear and anger in humans. Psychosomatic Medicine, 15, 433-422.

Campbell, E., & Jones, G. (2002). Sources of stress experienced by elite male wheelchair basketball players. Adapted Physical Activity Quarterly, 19, 82-99.

Canon, W. B. (1932). The wisdom of the body. New York: Norton.

Gould, D., Jackson, S., & Finch, L. (1993). Sources of stress in national champion figure skaters. Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 15, 134 - 159.

Hohmann, G. W. (1966). Some effects of spinal cord lesions on experiencing emotional feelings. Psychophysiology, 3, 143-156.

Lazarus, R. S. (1966). Psychological stress and the coping process. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Lazarus, R.S. (1999). Stress and emotion: A new synthesis. London: Free Association Books.

McGrath, J. E. (1970). Major methodological issues. In J. E. McGrath (Ed.), Social and psychological factors in stress (pp.19-49). New York, Holt: Rinehart & Winston.

Noblet, A. J., & Gifford, S. M. (2002). The sources of stress experienced by professional Australian footballers. Journal of Applied Sport Psychology, 14, 1-13.

Rainey, D. W., & Hardy, L. (1999). Sources of stress burnout and intention to terminate among rugby union referees. Journal of Sports Sciences, 17, 797-806.

Patmore, A. (1986). Sportsmen under stress. London: Stanley Paul.

Scanlan, T. K., Stein, G. L., & Ravizza, K. (1991). An in-depth study of former elite figure skaters: III. Sources of stress. Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 13, 103 - 120.

Selye, H. (1974). Stress without distress. Philadelphia: Lippincott.